Wak! It's been forever since I've updated around here. Sadly, I'm still under the gun with one project or another. But the least I can do is return briefly to a topic everyone's been asking for: the hunt for original titles. Like

Ozzie of the Mounted (1928), my fellow scholars and I will get our men—even if we lose our heads!

It's not a new discovery, of course, that many theatrical cartoons had their original title cards replaced for later reissue. The actual revelations are the original titles themselves—often because the cartoons' corporate owners dumped their originals, but sometimes because originals perished

in spite of the studios' best efforts. Luckily (see my lengthier discussion

here), in-depth research has brought back stragglers of all stripes.

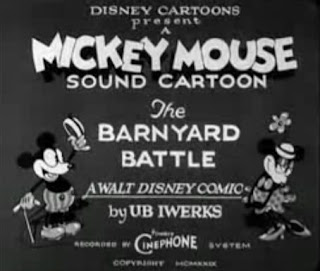

The Moose Hunt (1931) is a Mickey Mouse short for which Disney's original titles elements went missing at some point in the past. Here we see a faux-original title card recreated for a recent DVD set...

...and here is an actual original I more recently got the chance to see. In this case, the recreation attempt was about as close as could be imagined; the positioning of the words is different, but the proper card style was chosen and even the title font is similar.

Alas, sometimes the re-creator can't be quite as prescient. In the case of

Fiddlin' Around (1930), it's new knowledge that the cartoon was called that from the start. Studio records suggested that Mickey's violin-recital short was titled "Just Mickey" in its first release, and the faux title for DVD reflected this conventional wisdom:

But the CW isn't always right. The late Denis Gifford was the first to show me theatrical materials that suggested

Fiddlin' Around as the 1930 release title, and now we get a look at the original title card as well:

Interestingly, this shows that the first and second seasons of Columbia Mickeys had slightly different card styles. The background is darker on this 1930 episode (as with a few more that I'll share later on); much of the white lettering lacks a black outline; and most critically there's an effort to make the text on the chalkboard look like it's Mickey's own work. Better take some handwriting courses there, Mick.

Hm, and maybe you ought to get some plastic surgery while you're at it:

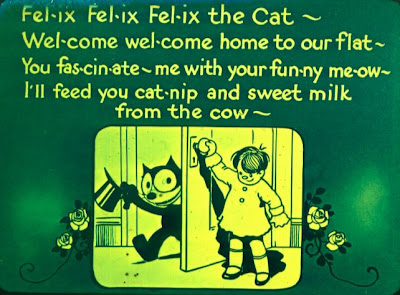

Thanks to research buddy Cole Johnson and collector Ralph Celentano, above we have an item I'd

never seen before—the 1930 Columbia reissue card for a Celebrity-era (1928-29) Mickey cartoon. While I'm not aware of an original Celebrity card surviving for

When the Cat's Away (1929), others hold out from the period:

With no extended knowledge on the matter just yet, I'll make an educated guess that Columbia staffers—rather than anyone at Disney—drew up that new title card for

Cat's Away (and, presumably, other Celebrity Mickey shorts). It's hard to imagine anyone on Uncle Walt's per diem transforming the studio stars into possums.

Of course, sometimes you didn't change species when your title card was remade. You just went from professionally drawn to fourth-grade level. Here's Dick Huemer's Toby the Pup as seen on reissues...

...and here's the hound as viewed by cinemagoers in 1931:

Should I be disturbed that Toby's feet look as much like hands on the original card as on the fake? I'm just not sure why he had to wear shoes with toes. Maybe Pervis the Goat ate all the normal shoes in the area—in

Circus Time (1931), he eats one of Toby's gloves.

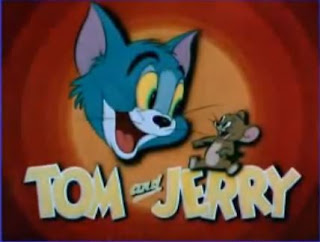

Gotta dash back to meeting deadlines, but I'd be a boob if I didn't go without delivering another item I'd promised for awhile—one more early Tom and Jerry title card. Most of us know

The Zoot Cat (1944) as looking like this reissue print:

But here's what audiences saw in 1944. Dig that color, squares. Go man, go go go:

For completeness' sake, here also is

Fraidy Cat (1942), with a rare intro card that we've already seen on the earlier

Midnight Snack (1941).

That's it for now—but there are more discoveries being made all the time. Sometimes, as my friend

Tom Stathes is always showing me, certain reissues are interesting, too:

Yes, that's a Columbia-era short with the United Artists title design. But some things are worth the wait...

Update, October 18: I'd formerly pictured an MGM lion card for

The Zoot Cat that understandably misled some of you—the lion was a circa 1940 card, while the cartoon is from 1944.

Thad K, who has looked at this print as well, remembered that its lion opening had in fact been spliced on from a different source.

Zoot Cat almost certainly had a standard 1944-era opening as seen on

this print of

Screwball Squirrel (1944).

Another big blog entry coming soon, I promise; but I'd be remiss not to draw your attention to this update of my earlier Halloween post. Following on the challenge I gave you there, I've now got some in-depth analysis of 1920s production methods with—I hope—some interesting observations.

Another big blog entry coming soon, I promise; but I'd be remiss not to draw your attention to this update of my earlier Halloween post. Following on the challenge I gave you there, I've now got some in-depth analysis of 1920s production methods with—I hope—some interesting observations.